A growing chorus of education researchers, pundits and “science of reading” advocates are calling for young children to be taught more about the world around them. It’s an indirect way of teaching reading comprehension. The theory is that what we grasp from what we read depends on whether we can hook it to concepts and topics that we already know. Natalie Wexler’s 2019 best-selling book, The Knowledge Gap, championed knowledge-building curricula and more schools around the country, from Baltimore to Michigan to Colorado, are adopting these content-filled lesson plans to teach geography, astronomy and even art history.

Makers of knowledge-building curricula say their lessons are based on research, but the truth is that there is scant classroom evidence that building knowledge first increases future reading comprehension.

In 2023, University of Virginia researchers promoted a study of Colorado charter schools that had adopted E.D. Hirsch’s Core Knowledge curriculum. Children who had won lotteries to attend these charter schools had higher reading scores than students who lost the lotteries. But it was impossible to tell whether the Core Knowledge curriculum itself made the difference or if the boost to reading scores could be attributed to other things that these charter schools were doing, such as hiring great teachers and training them well.

More importantly, the students at these charter schools were largely from middle and upper middle class families. And what we really want to know is whether knowledge building at school helps poorer children, who are less likely to be exposed to the world through travel, live performances and other experiences that money can buy.

A new study, published online on Feb. 26, 2024, in the peer-reviewed journal Developmental Psychology, now provides stronger causal evidence that building background knowledge can translate into higher reading achievement for low-income children. The study took place in an unnamed, large urban school district in North Carolina where most of the students are Black and Hispanic and 40% are from low-income families.

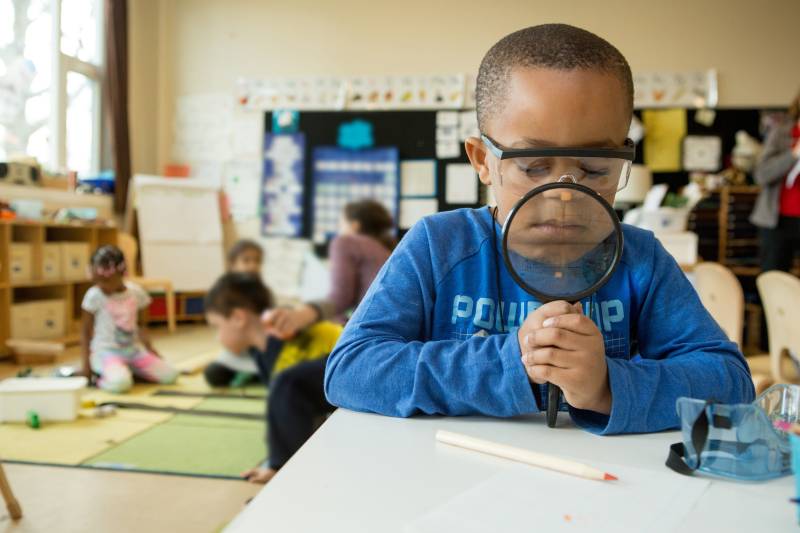

In 2019, a group of researchers, led by James Kim, a professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education, randomly selected 15 of the district’s 30 elementary schools to teach first graders special knowledge-building lessons for three years, through third grade. Kim, a reading specialist, and other researchers had developed two sets of multi-year lesson plans, one for science and one for social studies. Students were also given related books to read during the summer. (This research was funded by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, which is among the many funders of The Hechinger Report.)

The remaining 15 elementary schools in the district continued to teach their students as usual, still delivering some social studies and science instruction, but not these special lessons. Regular reading class was untouched in the experiment. All 30 schools were using the same reading curriculum, Expeditionary Learning, which follows science of reading principles and teaches phonics.

COVID-19 hit in the middle of the experiment. When schools shut down in the spring of 2020, the researchers scrapped the planned social studies units for second graders. In 2021, students were still not attending school in person. The researchers revised their science curriculum and decided to give an abridged online version to all 30 schools instead of just half. In the end, children in the original 15 schools received one year of social studies lessons and three years of science lessons compared to only one year of science in the comparison group.

Still, approximately 1,000 students who had received the special science and social studies lessons in first and second grades outperformed the 1,000 students who got only the abbreviated online science in third grade. Their reading and math scores on the North Carolina state tests were higher not only in third grade, but also in fourth grade, more than a year after the knowledge-building experiment ended.

It wasn’t a huge boost to reading achievement, but it was significant and long-lasting. It cost about $400 per student in instructional materials and teacher training.

Timothy Shanahan, a literacy expert and a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago who was not involved in this research or the development of these science lessons, praised the study. “The study makes it very clear (as have a few others recently) that it is possible to combine reading with social studies and science curriculum in powerful ways that can improve both literacy and content knowledge,” he said by email.

Connecting background knowledge to reading comprehension is not a new idea. A famous 1987 experiment documented that children who were weaker readers but knowledgeable about baseball understood a reading passage about baseball better than children who were stronger readers but didn’t know much about the sport.

Obviously, it’s not realistic for schools to attempt to familiarize students with every topic they might encounter in a book. And there is disagreement among researchers about how general knowledge of the world translates into higher reading performance.

Kim thinks that a knowledge-building curriculum doesn’t need to teach many topics. Random facts, he says, are not important. He argues for depth instead of breadth. He says it’s important to construct a thoughtful sequence of lessons over the years, allowing students to see how the same patterns crop up in different ways. He calls these patterns “schemas.” In this experiment, for example, students learned about animal survival in first grade and dinosaur extinction in second grade. In third grade, that evolved into a more general understanding of how living systems function. By the end of third grade, many students were able to see how the idea of functioning systems can apply to inanimate objects, such as skyscrapers.

It’s the patterns that can be analogized to new circumstances, Kim explained. Once a student is familiar with the template, a new text on an unfamiliar topic can be easier to grasp.

Kim and his team also paired the science lessons with clusters of vocabulary words that were likely to come up again in the future – almost like wine pairings with a meal.

The full benefits of this kind of knowledge building didn’t materialize until after several years of coordinated instruction. In the first years, students were only able to transfer their ability to comprehend text on one topic to another if the topics were very similar. This study indicates that as their content knowledge deepened, their ability to generalize increased as well.

There’s a lot going on here: a spiraling curriculum that revisits and builds upon themes year after year; an explicit teaching of underlying patterns; new vocabulary words, and a progression from the simple to the complex.

There are many versions of knowledge-rich curricula and this one isn’t about exposing students to a classical canon. It remains unclear if all knowledge-building curricula work as well. Other programs sometimes replace the main reading class with knowledge-building lessons. This one didn’t tinker with regular reading class.

The biggest challenge with the approach used in the North Carolina experiment is that it requires schools to coordinate lessons across grades. That’s hard. Some teachers may want to keep their favorite units on, say, growing a bean plant, and may bristle at the idea of throwing away their old lesson plans.

It’s also worth noting that students’ math scores improved as much as their reading scores did in this North Carolina experiment. It might seem surprising that a literacy intervention would also boost math. But math also requires a lot of reading; the state’s math tests were full of word problems. Any successful effort to boost reading skills is also likely to have positive spillovers into math, researchers explained.

School leaders are under great pressure to boost test scores. To do that, they’ve often doubled time spent on reading and cut science and social studies classes. Studies like this one suggest that those cuts may have been costly, further undermining reading achievement instead of improving it. As researchers discover more about the science of reading, it may well turn out to be that more time on science itself is what kids need to become good readers.

This story about background knowledge was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Proof Points newsletter.

http://dlvr.it/T3vhbn

Latest Update

4/sidebar/recent

Popular Posts

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

How arts education builds better brains and better lives

5/02/2023 09:05:00 pm0

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️Educational News

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️Educational News

College completion rates are up for all Americans, but racial gaps persist

2/20/2023 05:12:00 am0

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Social Media Is Fueling a Tween Skin Care Craze. Some Dermatologists Are Wary

7/15/2024 09:02:00 am0

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️Educational Lessons

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️Educational Lessons

The Truth About Physical Education and What It Means For Your Kids

1/03/2023 06:00:00 pm0

* We promise that we don't spam !

❚ Sections By Country

❚ Labels

About Us

All Tips and Health is a Learning Portal. We will only provide you with interesting content that you will enjoy. We are dedicated to providing you with the best Educational Guidelines, Recommendations, Health Tips, and More, with a focus on dependability, Health, and education. We're working hard to turn our passion for education, and health tips into a successful internet platform. We hope you like our Educational & Health Tips as much as we enjoy giving them to you. We Thank You!

Product Services

Services

Footer Menu Widget

Footer Copyright

Design by - Blogger Templates | Distributed by Small Business

#buttons=(Accept !) #days=(1)

Please Support Us, By Clicking On Any Of the Ads That Picks Your Interest Before leaving, Cause It Goes A Long Way To Support Us In Bringing You Good Quality Content. THANK YOU! Our website uses cookies to improve your experience. Learn More

Accept !