Students’ race and ethnicity affect their chances of earning a college degree, according to several new reports on higher education released in January and February 2023. However, the picture that emerges depends on the lens you use. College degrees are increasing among all racial and ethnic groups, but white and Asian Americans are far more likely to hold a college degree or earn one than Black, Hispanic or Native Americans.

Earning a college degree involves two steps: starting college and finishing college. Before the pandemic, white, Black and Hispanic Americans were enrolling in college at about the same rates, especially when unemployment was high and jobs were hard to find. (Asian Americans enrolled in college at much higher rates.) The bigger distinction is that once a student has started college, the likelihood of making it through the coursework and tuition payments and ultimately earning a degree varies so much by race and ethnicity.

First, let’s begin with enrollment. There are two ways to look at this. One is to see how the demographic makeup of college campuses has changed over time, becoming less white and more Hispanic. The pie charts below were produced in January by the National Student Clearinghouse, a nonprofit organization that provides data reporting services to colleges. In conjunction with these services, it monitors trends in higher education by aggregating the data submitted by more than 3,600 institutions, representing 97 percent of the students at the nation’s degree-granting colleges and universities. Earlier this year, the organization launched a DEI Data Lab site to put a spotlight on how college enrollment, persistence and completion vary by race and ethnicity.

In 2011, as the pie chart on the left shows, more than 60 percent of the nation’s 20.6 million college students were white, according to an estimate by the National Student Clearinghouse. By 2020, the year represented by the pie chart on the right, the total number of college students had fallen to 17.8 million and the share of white students had dropped by almost 9 percentage points to 52 percent, still a majority. During the same period, the share of Hispanic students grew from 14 percent to 21 percent, and the share of Black students remained constant at just under 14 percent. Asian students increased from 5 to 7 percent of the college population. This represents all undergraduate college students, both younger students entering straight after high school and older nontraditional students, studying full-time and part-time, and attending both four-year universities and two-year colleges.

The 2011 figures are rough estimates because only one out of five colleges reported race and ethnicity of students to the Clearinghouse. Today, more than three out of five colleges report on the race and ethnicity of their students to the Clearinghouse. (For the original version of this pie chart, click here.)

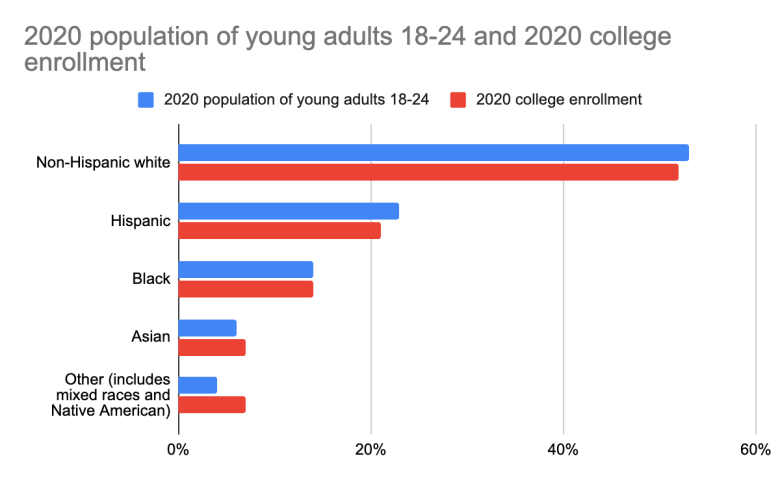

How should we think about these college enrollment numbers? Do they largely mirror each racial and ethnic group’s share of the population? I was surprised to learn that the answer is yes – with a few caveats. Asian Americans are slightly overrepresented on college campuses and Hispanic Americans are slightly underrepresented.

I created this chart below, comparing the National Student Clearinghouse’s college enrollment data for 2020 with the young adult population, as reported by the U.S Census, so you can see how closely college enrollment tracks actual demographics.

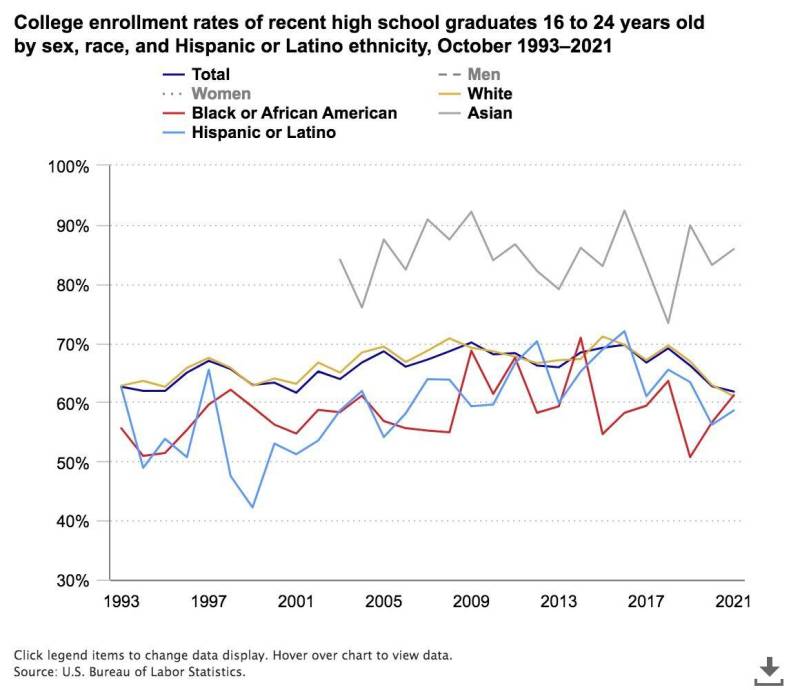

Another way to look at college enrollment is to see how many young adults enroll in college. The chart below, by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, shows that the college enrollment rates of Black and Hispanic young adults improved after the 2008 recession, and approached the college going rate of white Americans. Roughly 60 percent of young Black, Hispanic and white Americans are trying for a college degree. The college going rate for Asian Americans is much higher; more than 80 percent enroll. The zigs and zags in this chart show how college going among Hispanic and Black Americans is influenced by business cycles.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics obtains enrollment data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly survey of households conducted by the Bureau of Census. (Here is the chart on the BLS site.)

When jobs are plentiful, many low-income students may join the labor force and defer their higher education. That especially reduces enrollments among Black and Hispanic young adults, among whom poverty rates are higher. When unemployment is high, more young adults enroll at college, particularly at two-year community colleges. Most recently, during the pandemic, many young Americans deferred college to help support or take care of their families. Some students chose to wait until in-person classes resumed.

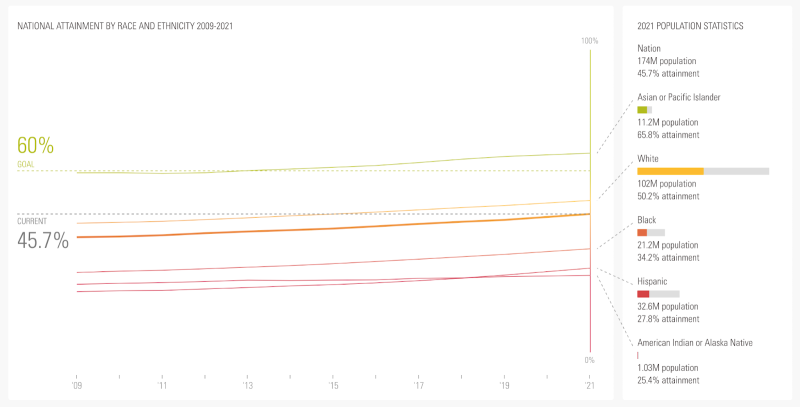

Going to college is one thing; finishing it is another. This fourth chart, produced by the Lumina Foundation, shows that over time, more Americans of every race and ethnicity are earning college degrees. The Lumina Foundation is a private foundation that seeks to increase the number of college graduates and was formed through the sale of Sallie Mae, which created, serviced and collected monthly payments on student loans. It is also among the many funders of The Hechinger Report.

Share of adult population, ages 25-64, with college degrees

This chart above, originally published here on Jan. 31, is based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. It tracks the percentage of adults 25 to 64 with two-year associate and four-year bachelor’s degrees. The share of Americans with a college degree rose from 38 percent in 2009 to nearly 46 percent in 2021 – an increase of eight percentage points.

Every race and ethnicity saw gains. The eight-percentage point gain was the same for both Black and white adults.

But racial gaps continue. In 2021, there remained an enormous 40 percentage point difference between Asian American adults, among whom 66 percent have a college degree, and Native American adults, among whom only 25 percent have a college degree. Among Black adults, 34 percent have college degrees. Among Hispanic adults, it’s 28 percent and among white adults, it’s 50 percent.

Improvements in college attainment can seem slow because graduation rates are much lower among Americans over 35. It takes years for higher college graduation rates among younger adults to raise overall college numbers. College attainment rates have jumped the fastest among young Hispanic adults under age 35, rising from below 20 percent in 2009 to above 30 percent in 2021. Courtney Brown, the chief data and research officer at Lumina, credits a variety of support programs, from tutoring to food pantries, and the convenience of online courses to explain why more young people are graduating, despite rising tuition costs. “Colleges are trying to serve students better,” said Brown. “Even the way they staff colleges, not all on getting enrollments but having more success coaches available and counselors helping students get to the finish line.”

Still, Brown acknowledges that it’s been difficult to make a dent in the stubborn gaps in college attainment between people of different races and ethnicities. “Unfortunately, everyone is increasing,” Brown said. “And so we are not seeing those gaps reduced.”

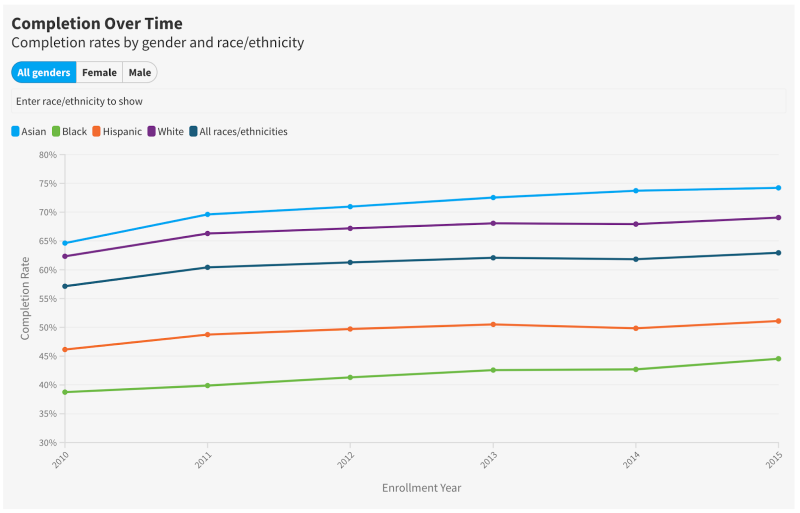

The National Student Clearinghouse’s DEI Data Lab also shows this completion problem starkly.

This chart tracks cohorts of students who began college at the same time and calculates how many of them earned any college degree within six years. Among students who started college in the fall of 2010, 62 percent of white students completed a degree by the summer of 2016, compared with only 39 percent of Black students. That’s a giant 23 percentage point gap, and a sign that a disproportionate number of Black students are dropping out of college in debt. Completion rates improved considerably for students who started college in 2015, but large gaps remain. Almost 70 percent of white students completed a degree by the summer of 2021, but only 45 percent of Black students hit this milestone. The Black-white college completion gap actually widened slightly from 23 to 24 percentage points.

The reasons for why completion rates remain much lower for Black, Hispanic and Native American students are complex. These students are more likely to attend community colleges, which have lower funding per student and fewer support services. Many students weren’t adequately prepared in high schools to handle college-level coursework, especially in math.

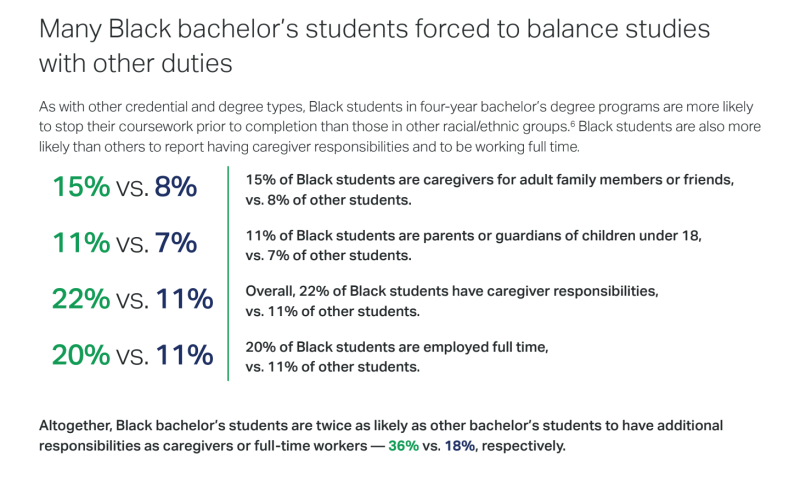

A poll of Black college students by Gallup-Lumina, released on Feb. 9, found that 21 percent of Black students report feeling discriminated against frequently or occasionally at the college they are attending, and that 45 percent have considered dropping out in the past six months. Black students in bachelor’s programs are far more likely to juggle family and work responsibilities alongside their studies.

“Black students are encountering so much more discrimination, and they have multiple responsibilities that no other race or ethnicity really has,” said Lumina’s Brown. “A lot of it is that Black students are more likely to have children. Working full time, having children and trying to get a bachelor’s degree at the same time is just obviously overwhelming.”

On Feb. 2, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center released the most recent college enrollment numbers for 2022. Undergraduate enrollment for both white and Black students fell for the fifth straight year, while enrollment of Hispanic and Asian students at public two-year colleges improved. However, their numbers are below pre-pandemic levels. For example, there were roughly 975,000 Hispanic students enrolled in public two-year colleges, also called community colleges, in the fall of 2022, up from 944,000 in the fall of 2021, but considerably down from 1.14 million in 2019. (Click here and navigate to the demographics tab for these fall 2022 charts.)

And here’s a startling data point: Black student enrollment at two-year community colleges declined by a staggering 44 percent, from 1.2 million in 2010 to 670,000 in 2020, according to a Sept. 2022 report by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a think tank that studies policy issues affecting Black Americans.

Fewer students at college now certainly means fewer college-educated adults in the years ahead. And that is not a promising future.

This story about higher ed data was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.