View the full episode transcript.

Zook, a high schooler in Rochester, NY in the 1990s, found her dreams of competing in city and state basketball competitions shattered when allegations of class-skipping led to the school revoke the team’s game record. In her frustration, Zook punched a teacher and was expelled. However, according to Bettina Love, a professor at Columbia University Teachers College, Zook’s outburst was a culmination of years of neglect and mistreatment within the education system.

“She doesn’t really punch a teacher for that particular incident. It [was for] all incidents: going through school for the last 13 years and not having one teacher tell her that she was bright, not having one teacher take any type of care, having a teacher in middle school body slam her to the ground and put her in a chokehold,” recounted Love, who played basketball with Zook and looked up to her teammate and friend.

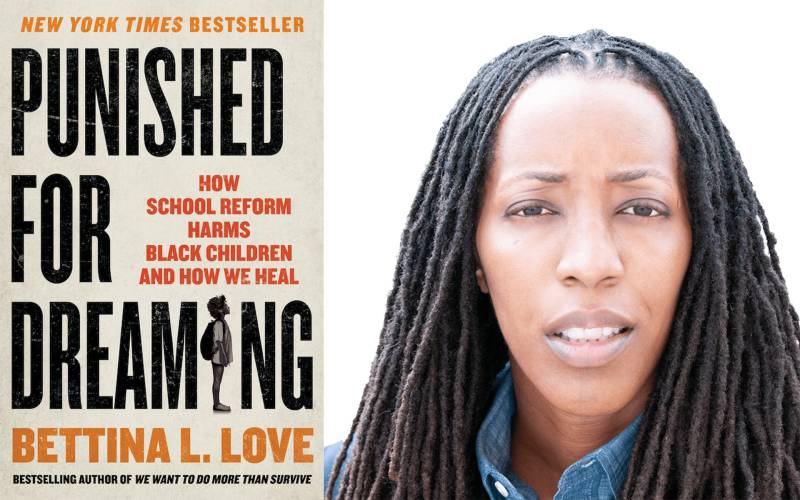

Zook’s experience was the impetus for Love’s book, Punished for Dreaming: How School Reform Harms Black Children and How We Heal, about the adverse effects of 40 years of education reform on Black students. Love highlights the experiences of many Black students, like Zook, navigating a flawed system. “I thought it was important to use real people’s lives to talk about school reform,” said Love, who, as an abolitionist educator, believes schools must undergo structural changes in order to serve all students. Throughout the book, she outlines solutions at the teacher, administrator and policy levels.

The decline of “a glorious era in Black education”

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas was a landmark Supreme Court decision that marked the end of the “separate, but equal” precedent for segregated schools. While celebrated as a civil rights victory, Love argues that it also marked the decline of a glorious era in Black education. Before the historic ruling, there were over 80,000 Black educators teaching about 2 million Black children.

“Not only were Black teachers teaching, they were highly credentialed, highly certified and were amazing,” said Love. After Brown v. Board, over 38,000 Black educators lost their jobs. The relationships and curriculum they cultivated were lost. “If you understand how racism works and how anti-blackness works, understanding how the gutting of Brown happened is not really hard,” said Love. “If I did not want my child to sit next to a Black child, I’m certainly not going to let a Black teacher teach them,” said Love.

As the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board approaches, the numbers of Black educators remain low, with Black teachers making up nearly 6% of the teaching workforce, according to a federal survey of the 2020-2021 school year. Research shows that students of all races tend to view Black teachers more positively than white teachers. “It has been a loss not only for Black students, but really all students,” explained Love. “Brown was really the impetus that started the destruction of Black education in this country.”

Reagan-era shifts in education

Ronald Reagan’s presidency in the 1980s brought about lasting changes to education, including significant cuts to funding. A report commissioned by his administration, “A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform,” said that US students were being out-performed and that educational standards were declining and led to policy shifts such as increased emphasis on standardized testing and enforcement of stringent graduation requirements. “This probably is one of the most consequential education reports of our time,” said Love.

Another report, “Chaos in the Classroom: Enemy of American Education,” said many students were victims of crimes at schools and schools needed better discipline practices. According to Love, this report laid the groundwork for the introduction of police officers in schools. “You start to see how education reform and crime reform begin to converge,” said Love. “Reagan was really the linchpin of merging education reform with crime reform.”

Love and others have critiqued these reports, pointing out alarmist language and misleading data. For example, at the time that “A Nation at Risk” was published, more students than ever were graduating high school and attending college. Love added that even if the report was an accurate representation of the educational landscape, harsher discipline could not achieve the desired results. “The solutions were never going to get us towards any type of educational justice or higher test scores,” she said. “[The solutions] were just punitive and anti-Black to the core.”

Strategies for overcoming challenges in education

Despite the critical need for funding, Love noted that Black schools receive less funding on average than predominantly white schools. She also pointed out that teachers’ compensation has not kept pace with other professions. Recent data shows 1 in 5 teachers moonlight and that teachers spend anywhere from $500 to $1000 dollars a year on their own supplies. Love said that teachers across the country are not only going on strike to get higher pay, but also for essentials like better air quality in their schools and clean water. However, both Republicans and Democrats rejected President Joe Biden’s plan to triple Title 1 funding which would have tripled per pupil spending. “We actually need politicians who are going to actually fight for teachers, fight for parents, fight for students and understand historical inequalities,” said Love.

Acknowledging the dramatic influence of education policies on Black lives, Love suggested reparations as a form of compensation for the harm done. “Another word for reparations is repair,” she said. California is the only state so far that has put action behind the idea of reparations. Love advocates for monetary compensation to Black individuals. “It’s a check to say we have done harm to you, your family, your community, and it has changed the course of your life. And we want to start to repair,” said Love.

People are divided on whether reparations are the right thing to do. “If you can’t see black folks as beautiful and worthy, then reparations [will be] hard for you,” said Love. “If folks know what we’ve done and what we continue to do and you see how this country has treated us, then you understand why reparations are important.”

In the face of systemic challenges, Love encouraged teachers to prioritize personal care through activities such as yoga, meditation and therapy. “We need teachers well in the classroom,” said Love. “We got to be well to show up for our kids when we know we are teaching in a system that is proliferating their destruction.” She said that administrators can help teachers take care of themselves by limiting superfluous work so that teachers can do what they need to do.

Love also emphasized the importance of treating children as children, noting that often Black and Brown children are treated – and even punished – like adults. She said that sometimes educators can have outsized reactions to things that are developmentally appropriate for kids. “They’re going to get on your nerves. You’ll tell them not to touch something and they’re going to touch it,” Love said. “We have to get back as a culture to seeing children and treating children and protecting children as children. If we did that, our policies would follow that. Our books, our classroom rules, all those things would follow.”

Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Nimah Gobir: Welcome to MindShift, the podcast where we explore the future of learning and how we raise our kids. I’m Nimah Gobir.

Nimah Gobir: As caregivers and educators, we’re likely used to interacting with schools in the day to day sense. It’s easy to forget that our experiences of school today are built on decades of history. And that’s what I’m here to talk to Dr. Bettina Love about. She’s a professor at Teachers College in Columbia University.

Nimah Gobir: Her recently released book, Punished for Dreaming, explores the disproportionate impact of education policies on Black students. If you’ve ever wondered why certain issues in education persist, Bettina might be able to give you some answers. My conversation with one of our favorite abolitionist educators, Bettina Love is up after the break.

Nimah Gobir: I’m going to start at the top of your book. There’s a story that you share about Zook in Punished For Dreaming. Can you tell me about how her experience shows the impact of educational policies on individual lives?

Bettina Love: Yeah, I thought it was important to really talk and use real people’s lives to talk about school reform. Zook is not only just a person in the book, but she’s one of my dearest, closest friends, and I was able to really understand how school policy impacts a person through Zook. And so Zook is a high school basketball star. She can do almost anything with a basketball. We are on our way to winning city and state. And then there’s this report or this allegation that Zook and some other male athletes are not going to class, they’re not attending class, and all our games are taken away. And then at the disciplinary hearing, Zook doesn’t have anybody there in her corner and she punches a teacher, but she doesn’t really punch a teacher for that particular incident. It’s all the incidents. It’s going through school for the last 13 years and not having one teacher tell her that she was bright, not having one teacher take any type of care, having a teacher in middle school body slam her to the ground and put her in a chokehold, 13 years of harm. And the book really opens with her story because it was a cautionary tale for me because I saw how you could be a superstar, you could score a lot of points, everybody could love you, but if you do something that people feel is so-called criminal, then you are punished for it in American schools. And she was really the impetus for this book.

Bettina Love: And so the book really wants us to put education in the same conversation as crime reform and welfare reform and immigration reform, like all these reform policies that we know historically have been hurtful to people of color. We don’t think about education reform like that. So it’s really trying to use people’s stories to go through the last 40 years of education reform and tell the story about what happened to us as Black people through education.

Nimah Gobir: Let’s take a look at Brown v Board of Education. I’m thinking about me as a kid in Walnut Creek, California, in public school, learning about Brown v Board. And I was taught that it was definitely a good thing with no downsides. Most people don’t know about the harm that it caused. Can you talk about how it shaped the trajectory of public education, specifically for Black students?

Bettina Love: It is probably one of the most consequential cases in the last 70, 80 years when it comes to education, that we don’t talk enough about. So it was really important in this book for me to talk about what we had before. Brown. Now, there is a glorious time in Black education before Brown versus Board of Education. Not only were Black teachers teaching, they were highly credentialed, they were teaching students to their highest potential. Black teachers made up 30 to 50% of teachers in the segregated South.

Nimah Gobir: Wow.

Bettina Love: We had upwards to around 90,000 black educators teaching about 2 million Black children, with almost 89% of them being Black women. So Brown pretty much guts black education. And so then we see almost 38,000 Black educators fired. Black teachers are pretty much out of the profession through policy, through reform. And here we are, you know, 70 years after Brown and in the last 40 years, black teachers have not made up words of 10% of teachers. Black male teachers are less than 2% of teachers, and black women are anywhere from 6 to 8%. All students benefit from teachers of color. And so it has been a disastrous loss not only for Black students, but really all students.

Nimah Gobir: That’s really important because it’s not that Black teachers aren’t qualified. It’s not that they don’t want to teach. It’s that they were pushed out of teaching positions.

Bettina Love: Right. And I want to be very clear, it’s not that white teachers can’t teach Black students. That’s not what we’re arguing. What we’re arguing is that 88% of the teaching force can’t be white. You need diversity, you need diversity of thought, a diversity of ideas. You need to at least have through your 13 years of schooling someone who looks like you and talks like you and understands you and sees you. It’s important. Representation is important. Your culture is important.

Nimah Gobir: Moving forward in history. I want to discuss the Reagan presidency and what you call the war on Black children. Can you voice over some key policies and shifts during this time and also the repercussions those had in education?

Bettina Love: Reagan was not very fond of the very ideas of public education. He was also not very fond of the government paying for public education. Reagan takes office 1982, he declares a war on drugs. 1983, Reagan releases another report. This probably is one of the most consequential education reports of our time, which is A Nation At Risk. A Nation At Risk says that this country, the United States of America, is failing behind most Western countries and that our education system is failing so badly that, you know, it could cause a war. This is just language of just fear mongering. By 1984, a year later, Reagan comes out with a report called Chaos in the Classroom, which says these children are so rude and disorderly, We need police in schools. That’s 82, 83, 84. Just those few entry points, you start to see how education reform and crime reform begin to emerge. We start to see this language that is extremely punitive, not only in crime reform, but it becomes punitive and education reform. Reagan was really the linchpin, really the start, the spark, of us really merging education reform with crime reform. And every situation that I just talked about from the war on drugs, A Nation At Risk, Chaos In The Classroom, the data was always flawed. These reform efforts and these policies were not created with data that actually was factual. Much of the data was misleading.

Nimah Gobir: With such alarmist titles, too. I feel like that’s the first giveaway.

Bettina Love: Chaos in the classroom! Like where? And, you know, and I think what people need to be clear about is that let’s say the data was correct. Okay? Let’s just say the data wasn’t misleading. Okay. If that’s what’s happening, the solution should not be: be punitive. The solution should have been, well, we need to hire more teachers. We need to pay teachers a living wage. We need to have smaller classrooms. Why is the solution “we need more police.” How has that got anything to do with the low test score that you’re talking about? Those things don’t go hand in hand.

Nimah Gobir: Given this historical context, I feel like at this point we’re sitting on a pile of punitive reform ideas. What does the educational landscape look like for Black students in particular, and what are some of the challenges Black students are facing because of these policies?

Bettina Love: Well, you know, I think many people would say, you know, the critical race theory bans the book bans. And those are serious things we have to be talking about. But I also want us to understand that in 2016, there was a report by Ed Bilder. And Ed Bilder came out and said that white schools in this country receive $23 billion more funding than nonwhite schools. We also know that students who need the most in this country get the least experienced teachers. 1 in 5 teachers, moonlight. Teachers around the country are deeply underpaid. We’ve seen teacher strikes all over the country last year, and I’m sure there’s going to be many more this year. Our schools have air pollutants in them that children can’t breathe. Our schools are talking about an achievement gap. We need babies in schools with clean air and clean water and credentialed teachers. We need schools where children can walk in and feel a sense of pride. And we also need schools where they can learn about themselves and the beauty of their history and who they are. Education, Right. Not right now. When you put all of that in context, it’s pretty dire.

Nimah Gobir: What I’m hearing in your answer is that a lot needs to happen on many different scales. What should we be looking at as far as – I mean, I’m scared to say policy reform at this point – but what should we be looking at on a national level? What needs to be done to address some of the issues that you outlined?

Bettina Love: A child in this country per pupil rate is like between 12 or $14,000. Like that’s what we get per pupil. Joe Biden is running and saying, listen, we need to increase Title one funding, per pupil funding by three times. So like making every child, particularly in low income schools, low income communities, you know, $30,000. Not only was that struck down, but it was struck down by the Democrats, too. Folks who say they are about justice and equity and equality are shooting down these type of policies. We got to be clear that there has been no party that essentially has been the party of education, has done some type of educational justice, liberation, thoughtful equality work. We actually need politicians who are going to actually fight for teachers, fight for parents, fight for students, understand inequality, understand historical inequalities, fight for funding, fight for resources. You cannot simply say that you’re going to hold education and teachers to these policies, to these laws, and then don’t have anything in the background to say how they’re going to support you.

Nimah Gobir: In your book, you make a case for reparations. Can you clarify what that means first for people who might be new to this concept and also what it might look like?

Bettina Love: Yeah. You know, I thought it was really important to try and write about something bold. So what I argue in this book is that if you look at the current education system just by generation, the last 40 years, harm has been done. The way Black students have been police and tested, expelled, funded, you have changed the trajectory of my life through education. Another word for reparations is repair. So how do you begin to repair this system? And the fullness of reparations is to end harm, is to atone for harm, is to start to think structurally how we say, “Hey, we did this. We know we did this. We’re apologizing because we did this. We’re compensating you because we did this. We’re going to end these policies that have done harm to you.” If you can’t see Black folks as beautiful and worthy, then reparations is hard for you. If you know who we are and you know our history and what we’ve done and what we continue to do and you see how this country has treated us even as we have kept creating and loving and inventing, then you will understand why reparations is important.

Nimah Gobir: Shifting the focus to educators and administrators. What actions can they take to make their classrooms more equitable and inclusive for black students? And I also want to acknowledge that I think it’s really hard to think about what to do at the teacher level when so much is happening at the policy level or so much isn’t happening at the policy level.

Bettina Love: I think the one thing teachers have to do on a very personal level is just take care of themselves. Drink your water, meditate, exercise. Do some yoga if you can. Find some time to really care about your wellbeing and yourself. Because we need teachers not only in the classroom. We need teachers well in the classroom. Right. Go to therapy, Indigenous practices, like we got to be well to show up for our kids when we know we are teaching in a system that is proliferating their destruction. So that is a really hard thing to show up every day, knowing that there are so many systems and structures and rules and policies and tests that are hurtful. Administrators have a lot of power too. So we need administrators to really understand what is necessary for a teacher and move that busy work to the side, so they can actually do what they need to do. But I would say the biggest thing that teachers and administrators can do tomorrow is remember that you have children in front of you. And what we see now is that seven year olds and five year olds and 15 year olds are treated, particularly if they’re Black and brown like adults. We got to remember that these are actual children.

Nimah Gobir: I love that double pronged approach. It’s like, number one, if this meeting could be an email, make it an email. And number two, let kids be kids. My last question for you is what is your vision for the future of education in America? What do you hope to see in the years to come?

Bettina Love: What I would hope to see in the years to come is that the folks who say they are truly concerned about education, make the policies, make the laws would actually ask Gholdy Muhammad, Dena Simmons, Yolanda Sealy Ruiz, Gloria Ladson Billings, Cynthia Dillard, Adrian Dixon. Like, I would really like them to understand that there is a profound piece of knowledge – Linda Darling-Hammond – there’s a profound piece of knowledge – Pedro Negara. Like we can go on and on and on about these educational giants. There’s folks who have answers and solutions. Pick up our writings, ask us a question. We would like to be in these conversations. We got years of data, experience and knowledge. And so that’s what I would really want to see. I would want to see the folks who have invested their careers and their time and have done this work really be the ones who are asked, charged with doing the educational work, the folks in the communities and the parents and the aunties and the grandmas who have knowledge. I would love to see us actually ask a question.

Nimah Gobir: Oh, I love that. I want whatever new policy that comes out to be: Please ask Goldie Muhammad.

Bettina Love: Ask Goldie Muhammad. Right. There are just people who we know are amazing black educators, scholars doing this work. So I would love for them to be able to create policy on a federal level. These folks know what they’re talking about, know what they’re doing. Never called.

Nimah Gobir: I think MindShift’s audience is really going to appreciate the reading list you just gave them. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk today.

Bettina Love: Thank you so much. I’m glad we had this opportunity.

Nimah Gobir: Bettina Love’s book is called Punished for Dreaming. MindShift will have more minisodes coming down the pipeline to bring you ideas and innovations from experts in education and beyond. Don’t forget to hit follow on your favorite podcast app so you don’t miss a thing.

Nimah Gobir: If you like what you heard in this episode, I have recommendations for you. We did an episode with Micia Mosley about why every student deserves a black teacher. We’ve also done two episodes with Gholdy Muhammad.

Bettina Love: Ask Goldie Muhammad!

Nimah Gobir: The MindShift team includes me, Nimah Gobir, Ki Sung, Kara Newhouse and Marlena Jackson Retondo. Our editor is Chris Hambrick. Seth Samuel is our sound designer. We receive additional support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldana and Holly Kernan. MindShift is supported in part by the generosity of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and members of KQED. Thank you for listening.

http://dlvr.it/T18HGy

Latest Update

4/sidebar/recent

Popular Posts

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️Educational News

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️Educational News

College completion rates are up for all Americans, but racial gaps persist

2/20/2023 05:12:00 am0

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

How arts education builds better brains and better lives

5/02/2023 09:05:00 pm0

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Is AC the new ABC? As the country gets hotter, schools need upgrades

9/06/2023 04:12:00 am0

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Researchers Warn of Potential for Racial Bias in AI Apps in the Classroom

7/08/2024 05:39:00 am0

* We promise that we don't spam !

❚ Sections By Country

❚ Labels

About Us

All Tips and Health is a Learning Portal. We will only provide you with interesting content that you will enjoy. We are dedicated to providing you with the best Educational Guidelines, Recommendations, Health Tips, and More, with a focus on dependability, Health, and education. We're working hard to turn our passion for education, and health tips into a successful internet platform. We hope you like our Educational & Health Tips as much as we enjoy giving them to you. We Thank You!

Product Services

Services

Footer Menu Widget

Footer Copyright

Design by - Blogger Templates | Distributed by Small Business

#buttons=(Accept !) #days=(1)

Please Support Us, By Clicking On Any Of the Ads That Picks Your Interest Before leaving, Cause It Goes A Long Way To Support Us In Bringing You Good Quality Content. THANK YOU! Our website uses cookies to improve your experience. Learn More

Accept !