Ever since the pandemic shut down schools in the spring of 2020, education researchers have pointed to tutoring as the most promising way to help kids catch up academically. Evidence from almost 100 studies was overwhelming for a particular kind of tutoring, called high-dosage tutoring, where students focus on either reading or math three to five times a week.

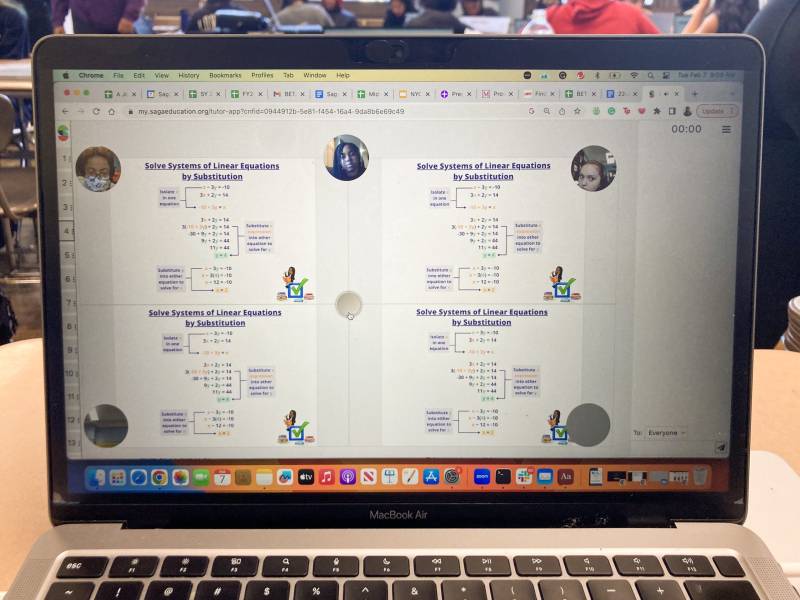

But until recently, there has been little good evidence for the effectiveness of online tutoring, where students and tutors interact via video, text chat and whiteboards. The virtual version has boomed since the federal government handed schools nearly $190 billion of pandemic recovery aid and specifically encouraged them to spend it on tutoring. Now, some new U.S. studies could offer useful guidance to educators.

Online attendance is a struggle

In the spring of 2023, almost 1,000 Northern California elementary school children in grades 1 to 4 were randomly assigned to receive online reading tutoring during the school day. Students were supposed to get 20 to 30 sessions each, but only one of five students received that much. Eighty percent didn’t, and they didn’t do much better than the 800 students in the comparison group who didn’t get tutoring, according to a draft paper by researchers from Teachers College, Columbia University, which was posted to the Annenberg Institute website at Brown University in April 2024. (The Hechinger Report is an independent news organization based at Teachers College, Columbia University.)

Researchers have previously found that it is important to schedule in-person tutoring sessions during the school day, when attendance is mandatory. The lesson here with online tutoring is that attendance can be rocky with even during the school day. Often, students end up with a low dose of tutoring instead of the high dose that schools have paid for.

However, online tutoring can be effective when students participate regularly. In this Northern California study, reading achievement increased substantially, in line with in-person tutoring, for the roughly 200 students who got at least 20 sessions across 10 weeks.

The students who logged in regularly might have been more motivated students in the first place, the researchers warned, indicating that it could be hard to reproduce such large academic benefits for all. During the periods when children were supposed to receive tutoring, researchers observed that some children – often ones who were slightly higher achieving – regularly logged on as scheduled while others didn’t. The difference in student behavior and what the students were doing instead wasn’t explained. Students also seemed to log in more frequently when certain staff members were overseeing the tutoring and less frequently with others.

Small group tutoring doesn’t work as well online

The large math and reading gains that researchers documented in small groups of students with in-person tutors aren’t always translating to the virtual world.

Another study of more than 2,000 elementary school children in Texas tested the difference between one-to-one and two-to-one online tutoring during the 2022-23 school year. These were young, low-income children, in kindergarten through 2nd grade, who were just learning to read. Children who were randomly assigned to get one-to-one tutoring four times a week posted small gains on one test, but not on another, compared to students in a comparison group who didn’t get tutoring. First graders assigned to one-to-one tutoring gained the equivalent of 30 additional days of school. By contrast, children who had been tutored in pairs were statistically no different in reading than the comparison group of untutored children. A draft paper about this study, led by researchers from Stanford University, was posted to the Annenberg website in May 2024.

Another small study in Grand Forks, North Dakota confirmed the downside of larger groups with online tutoring. Researchers from Brown University directly compared the math progress of middle school students when they received one-to-one tutoring versus small groups of three students. The study was too small, only 180 students, to get statistically strong results, but the half that were randomly assigned to receive individual tutoring appeared to gain eight extra percentile points, compared to the students who were assigned to small group tutoring. It was possible that students in the small groups learned a third as much math, the researchers estimated, but these students might have learned much less. A draft of this paper was posted to the Annenberg website in June 2024.

In surveys, tutors said it was hard to keep all three kids engaged online at once. Students were more frequently distracted and off-task, they said. Shy students were less likely to speak up and participate. With one student at a time, tutors said they could move at a faster pace and students “weren’t afraid to ask questions” or “afraid of being wrong.” (On the plus side, tutors said groups of three allowed them to organize group activities or encourage a student to help a peer.)

Behavior problems happen in person, too. However, when I have observed in-person small group tutoring in schools, each student is often working independently with the tutor, almost like three simultaneous sessions of one-to-one help. In-person tutors can encourage a student to keep practicing through a silent glance, a smile or hand signal even as they are explaining something to another student. Online, each child’s work and mistakes are publicly exposed on the screen to the whole group. Private asides aren’t as easy; some platforms allow the tutor to text a child privately in a chat window, but that takes time. Tutors have told me that many teens don’t like seeing their face on screen, but turning the camera off makes it harder for them to sense if a student is following along or confused.

Matt Kraft, one of the Brown researchers on the Grand Forks study, suggests that bigger changes need to be made to online tutoring lessons in order to expand from one-to-one to small group tutoring, and he notes that school staff are needed in the classroom to keep students on-task.

School leaders have until March 2026 to spend the remainder of their $190 billion in pandemic recovery funds, but contracts with tutoring vendors must be signed by September 2024. Both options — in person and virtual — involve tradeoffs. New research evidence is showing that virtual tutoring can work well, especially when motivated students want the tutoring and log in regularly. But many of the students who are significantly behind grade level and in need of extra help may not be so motivated. Keeping the online tutoring small, ideally one-to-one, improves the chances that it will be effective. But that means serving many fewer students, leaving millions of children behind. It’s a tough choice.

This story about online tutoring was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Proof Points and other Hechinger newsletters.

http://dlvr.it/T9c5HW

Latest Update

4/sidebar/recent

Popular Posts

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️Educational News

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️Educational News

College completion rates are up for all Americans, but racial gaps persist

2/20/2023 05:12:00 am0

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

How arts education builds better brains and better lives

5/02/2023 09:05:00 pm0

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Is AC the new ABC? As the country gets hotter, schools need upgrades

9/06/2023 04:12:00 am0

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Edwin Adjetey Ofori Crimson ☑️

Researchers Warn of Potential for Racial Bias in AI Apps in the Classroom

7/08/2024 05:39:00 am0

* We promise that we don't spam !

❚ Sections By Country

❚ Labels

About Us

All Tips and Health is a Learning Portal. We will only provide you with interesting content that you will enjoy. We are dedicated to providing you with the best Educational Guidelines, Recommendations, Health Tips, and More, with a focus on dependability, Health, and education. We're working hard to turn our passion for education, and health tips into a successful internet platform. We hope you like our Educational & Health Tips as much as we enjoy giving them to you. We Thank You!

Product Services

Services

Footer Menu Widget

Footer Copyright

Design by - Blogger Templates | Distributed by Small Business

#buttons=(Accept !) #days=(1)

Please Support Us, By Clicking On Any Of the Ads That Picks Your Interest Before leaving, Cause It Goes A Long Way To Support Us In Bringing You Good Quality Content. THANK YOU! Our website uses cookies to improve your experience. Learn More

Accept !